At the battle of Killiecrankie on 27 July 1689, Scottish government forces under the command of Major-General Hugh Mackay of Scourie were defeated by a Jacobite army loyal to the deposed King James commanded by John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee. It was the first battle of the Jacobite period and the bloodiest of the risings.

The Revolution of 1688

By 1688, three years into his reign, King James VII of Scotland and II of England was not a popular monarch and had aroused suspicion in both England and Scotland as a Catholic ruling over predominately Protestant subjects. James, a staunch believer in the ‘Devine Right of Kings’, was increasingly becoming autocratic and arbitrarily imposed several unpopular measures, including direct rule over the autonomous Scottish burghs. There was fear of civil unrest or worse, civil war and many looked to James’s protestant nephew and son-in-law, William of Orange, the stadtholder of the Netherlands, to defend ‘protestant liberties’ and restore parliamentary supremacy.

Following the birth of James’ son, James Francis Edward Stuart on 10 June 1688, a group of English lords, fearful of a Catholic absolute monarchy and the spectre of a succession of popish monarchs, officially invited William to England. William saw an opportunity to detach England from a possible alliance with France under Louis XIV — with who the Dutch were at war — and bring English troops, ships, and money to bear against the French. On 5 November 1688, William landed at Brixham in Devon with an army of around 15,000 troops. His force included the Scots-Dutch Brigade under Major-General Hugh Mackay of Scourie.

Before William’s invasion, James had ordered his Scottish army of around 3,700 under the command of Lieutenant-General James Douglas to march south to join up with his English forces assembling on Salisbury Plain. Lieutenant-General Douglas was one of many army officers who defected to William and this left his deputy, Major-General John Graham of Claverhouse, in command of the Scots Army.

Known as ‘Bluidy Clavers’ by his Presbyterian enemies following his part in the repression of the Covenanters in southwest Scotland, and ‘Dark John of the Battles’ by his highland allies, Claverhouse was a relation of James Graham, Marquis of Montrose who had led the highlanders to a string of victories for the royalist cause of James’ father Charles I during the civil war of the 1640s. Claverhouse had served under William of Orange while serving in the Scots-Dutch Brigade during the Franco-Dutch War (1672-78) and is reputed to have saved William’s life at the battle of Seneffe.

Claverhouse was created Viscount Dundee and was given command of James’s forces in Scotland. Claverhouse urged James to fight William, but it was to no avail. With his support melting away rapidly in the face of William’s advance on London, James fled to France on 23 December. James was welcomed at the court of Louis XIV who saw an opportunity to use the Stuart king to cause trouble for his enemy William of Orange. In fleeing the country, the English Parliament declared that James had abdicated the throne and a Convention in February 1689 offered the crown to William and his wife Mary as joint monarchs.

Returning to Scotland, Claverhouse found a country in turmoil. The removal of the Scots Army south had created a power vacuum, and it was clear that a civil war between the supporters of James and those of William was coming. Supporters of James became known as Jacobites, derived from Jacobus, the Latin for James. Those who supported William and Mary were known as Williamites.

The Revolution in Scotland

Scotland was a divided country on the issue of the crown. After the persecutions of the Covenanters in southern Scotland by the Stuarts, many Presbyterians were glad to see the back of James. James had also alienated many Episcopalians. However, the House of Stuart had ruled Scotland for over three centuries and despite his failings, there was still support for James and the senior line of the Stuarts. In 1689 most of this support came from the western highlands where ancient loyalties and tradition ran deep, despite the fact that the Gàidhealtachd had suffered at the hands of the Stuarts in the past.

A National Convention was assembled at Parliament House in Edinburgh on 14 March 1689 to determine the Scottish Crown. The assembly met under the shadow of the guns of Edinburgh Castle, held for King James by George, Duke of Gordon.

There was concern that the Tory Jacobites might attempt to seize the Williamite Whig members of the convention. This concern grew when Claverhouse lodged around 50 dragoons in the town not far from the assembly. To counter this threat, the Williamites summoned large numbers of armed Presbyterians from the southwest, along with clansmen from the Earl of Argyll’s estates, and lodged them in and around Parliament House.

When word reached the Convention that King James had landed in Ireland on 12 March intending to raise an army of Irish Catholics, there was fear that he may invade southwest Scotland. To counter the threat of a Jacobite invasion from Ireland orders were issued for muskets, pikes, and ammunition to be sent from the magazine at Stirling Castle to Glasgow where they would be distributed to the militia troops in the southwest. Two frigates from Glasgow were also sent to patrol the Irish coast.

To secure parliament and the capital, the Convention’s president, William, Duke of Hamilton ordered David Leslie, Earl of Leven to raise a regiment in Edinburgh to protect the city from the Jacobites. Within two hours Leven was able to recruit 800 men from among the southwest Presbyterians that had flocked to the capital. The first task for Leven’s new regiment was to blockade Edinburgh Castle.

A further eight regiments of foot would be raised in the coming weeks and months, along with troops of horse militia. Noblemen loyal to the new regime were given commissions to raise regiments. The Earl of Glencairn, Earl of Argyll, Earl of Mar, Viscount Kenmure, Lord Blantyre, Lord Bargany and Ludovic Grant all raised regiments of foot numbering 600 men, while the Earl of Angus raised 1,200 men.

At the Convention, the Lord Justice Clerk, Sir John Dalrymple claimed that James had forfeited the crown by his actions, listed in the Articles of Grievances. The Duke of Hamilton suggested that they should offer the crown of Scotland to William and Mary, and most of the assembly agreed.

Claverhouse threw his support in with James at the Convention but after it ruled in favour of William he knew that there was very little he could achieve by staying in Edinburgh. Fearful of appreciation and with rumours that there was a risk to his life, he left the city with his dragoons and headed to his home at Dudhope Castle near Dundee.

Concerned about the situation in Scotland, King William sent Major-General Hugh Mackay, a highlander from Scourie in Sutherland, to secure the country and take control of the military situation there. On 25 March, Mackay arrived at the port of Leith with his Scots-Dutch brigade and Lord Colchester’s regiment of horse. The Scots-Dutch brigade numbering 1,100, consisted of Mackay’s own regiment, Brigadier Barthold Balfour’s regiment, and Colonel George Ramsay’s regiment. The brigade was severely understrength as King William had ordered the experienced troops to be sent to reinforce his Dutch regiments.

While on his journey home, Claverhouse stopped for the night at a tavern in the town of Dunblane. Here he met Alexander Drummond of Balhaldie, the son-in-law of Sir Ewen Cameron of Lochiel, the legendary chief of Clan Cameron. Lochiel had sent Drummond with a message that several clans in the western highlands and islands had formed a confederacy to support King James and wished for Claverhouse to lead them.

Claverhouse continued on his journey to Dudhope and on 13 April, he raised the Scottish Royal Standard on Dundee Law, marking the beginning of the Jacobite Rising of 1689.

The Jacobite Rising of 1689

Claverhouse knew from Lochiel’s letter that he could rely upon the support of the Catholic and Episcopalian clans of Lochaber and the Isles so he first set out to secure the Episcopalian northeast and raise support there. He hoped that the lairds of the lowland northeast would also be able to provide cavalry for the Jacobite army. The northeast had been a royalist hotbed during the civil war of the 1640s and would provide large numbers of Jacobite recruits during the risings of 1715 and 1745, however, in 1689 the region was divided and Claverhouse would find little support.

In the meantime, Major-General Mackay had set out from Edinburgh with a detachment of the Scots-Dutch brigade a troop of horse intending on apprehending Claverhouse before he could raise men in the north for James’s cause. Prior to leaving, Mackay wrote to a number of northern magnates requesting that they move to block Claverhouse. These included John Murray, Marquis of Atholl was asked to raise 300 men to guard the vital Pass of Killiecrankie, and Charles Erskine, Earl of Mar who was requested to scour the Braes of Mar.

Leaving Dudhope, Claverhouse first travelled to Glen Ogilvy before heading to Keith, Elgin and then on to Forres. At Forres, he received information that some troopers in his old dragoon regiment now under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Livingstone planned to defect and join the Jacobite cause and he immediately headed back south with the intention of linking up with them. At Cairn o’ Mount he learned from intercepted letters that Major-General Mackay was moving upon him.

Foiling Mackay’s attempt to capture him, Claverhouse made his way to Inverness where he issued a summons in the name of King James for the loyal clans to muster on 18 May at Dalcomera in Lochaber. From Inverness, Claverhouse and his troop of dragoons moved rapidly south into Atholl and then into Perth before heading towards Dundee where Livingstone’s dragoons were now stationed. Claverhouse’s plan to entice the dragoons out to join with him was foiled and he withdrew to Lochaber and the mustering of the clans.

King William had stationed a number of Dutch and English regiments on the border with Scotland to serve as reinforcements should the government in Scotland request assistance. Claverhouse’s move on Dundee panicked the Convention and they requested Major-General John Lanier who commanded at Berwick to march to Edinburgh with Hastings’ and Leslie’s regiments of foot along with Lanier’s own cavalry regiment and Berkeley’s dragoons.

Mackay had marched through the northeast and arrived at Inverness where he sent orders to Brigadier Balfour in Edinburgh to send Colonel Ramsay and the rest of the Scots-Dutch brigade up to Inverness. Ramsay left Edinburgh and proceeded to Perth and then into Atholl before being forced to retire back to Perth since the way was blocked by hostile Athollmen.

Meanwhile, on 11 May, William and Mary accepted the crown of Scotland. The Convention became a full parliament and a new government was formed.

While the gathering at Dalcomera was impressive the clansmen were poorly armed. Military historian Stuart Reid highlights the fact that very few highlanders would have been armed with muskets and only the clan gentlemen would carry the basket-hilted broadsword and targe. The vast majority would have been armed with Lochaber axes, dirks, and pikes intended for close-quarter fighting.1

Claverhouse intended to spend some time training the highlanders in regular infantry tactics but Locheil advised against this. The Jacobites lacked firearms and gunpowder and there simply wasn’t enough time to train them in even the most basic of military tactics and manoeuvres. Locheil argued that the highlanders best chance of success was their famed highland charge which was described in his memoirs:

The highlanders are the only body of men that retain the old method, excepting in so far that they have of late taken the gun instead of the bow to introduce them into action: That so soon as they are led against the enemy, they come up within a few paces of them, and having discharged their pieces in their very breasts they throw them down, and draw their swords: That the attack is so furious, that they commonly pierce their ranks, put them into disorder, and determine the fate of the day in a few moments.2

On 16 May, a detachment from Bargany’s regiment defeated Jacobite forces at the battle of Loup Hill in northern Kintyre. The victory ensured government control over the strategically important Kintyre peninsula and hindered Jacobite reinforcements coming over from Ireland.

Claverhouse and his highland army marched into Badenoch on 25 May. They besieged and captured Ruthven Castle held by a company from Grant’s regiment before contemplating a move over to Aberdeen. The way to the eastern lowlands was open while Mackay was still based at Inverness, however, Claverhouse was struck down with dysentery and the Jacobite army withdrew back to Lochaber.

On 7 June, 200 government dragoons under Lieutenant-Colonel Thomas Livingstone intercepted a large party of Maclean clansmen near Boat of Garten. The Macleans, who had become separated from the main Jacobite force, took up position on a hill at Knockbrect. Livingstone dismounted his dragoons and sent them up the hill to engage the clansmen. The Maclean’s charged downhill and cut their way through before making their escape.

Mass desertions among the clansmen forced Claverhouse to disband his army on the understanding that the clans would muster again when he summoned them. He then retired to the home of Locheil at Achnacarry to recover from his illness.

Mackay, who had by now marched south from Inverness to Ruthven, believed that the Jacobites posed no immediate threat and he marched his army back to Inverness where he established a strong garrison consisting of Leslie’s and Grant’s regiments along with Livingstone’s dragoons.

Mackay wrote to the Scottish government advising them to establish a force of 2000 men in Argyllshire under the command of Archibald Campbell, Earl of Argyll. Argyll’s command would consist of his own regiment, Glencairn’s and Angus’s regiments along with Bargany’s detachment from Kintyre and four troops of horse.

Mackay then made his way back to Edinburgh, arriving there on 12 July and set about getting everything ready for his expedition to Lochaber.

Highland Warfare during the Jacobite Rising of 1689: The front rank of the highland clan regiments would have comprised the clan’s warrior elite who would be reasonably well armed with muskets, the iconic highland broadsword, and targes. These men would literally be the cutting edge of the ‘Highland Charge’. The bulk of the regiment standing behind them would have comprised less motivated men drawn from the chief’s estates. These men would have little to no training and would be armed with an assortment of weapons such as Lochaber axes, dirks, pikes, and farming implements, and some would have initially had no weapons at all, as was the case at Tippermuir in 1644 where some highlanders resorted to using stones.3

Mackay’s expedition to the highlands

Mackay’s intention now was to march through Atholl and then continue on to Inverlochy in Lochaber where he, like General Monck, would construct a fort and place a garrison with the purpose of subduing the Lochaber clans. Before leaving Edinburgh, Mackay sent orders to Argyll to march his newly established force north and to rendezvous with him in Lochaber where their joint forces would crush the rising in its heartland before the clans fully mustered again.

Fearing that Argyll might attack him in Lochaber, or that a pincer movement by both Argyll and Mackay was developing, Claverhouse mustered the clans with a general rendevous set for 29 July. He planned to move rapidly into Atholl before Mackay arrived there in sufficient strength. Claverhouse was also hopeful that a decisive move south would see John Campbell, Earl of Breadalbane and his men join with the Jacobites.

Writing to Lord John Murray who held Blair Castle for his absent father, the Marquis of Atholl, Claverhouse urged him to declare for King James and raise the Athollmen. Murray did not respond and fearing his loyalty was with King William, Claverhouse ordered the marquis’s factor, Patrick Stewart of Ballochie, to raise a force of men and seize the strategically important stronghold. With Blair Castle in Jacobite hands, Mackay’s direct communication route to Inverness and the north was cut and he would now be forced to deal with the situation there before moving on to Inverlochy.

To support Claverhouse’s rising, King James sent Brigadier-General Alexander Cannon, a lowland Scot from Galloway, along with a number of officers and Colonel Nicolas Purcell’s regiment to Scotland from Ireland. Embarking on three French frigates the force set sail from Belfast. Off the coast of Kintyre, they ran into frigates of the Scots Navy and the French were forced to put Cannon and his troops ashore on the south side of the Isle of Mull.

Cannon and his men crossed the island and reached the Maclean stronghold of Duart Castle on 12 July. From here they took boats across the Sound of Mull and landed in Morvern before sailing across Loch Linnhe to Inverlochy at the head of Loch Linnhe where he joined with Claverhouse. Shortly after Cannon left Mull a Royal Navy squadron under Captain Rooke arrived to bombard Duart. The English warships had been summoned into Scottish waters to aid in anti-Jacobite operations on the western seaboard as the frigates of the Royal Scots Navy were away patrolling the Irish coast.

With speed and surprise essential, and unable to wait for all of the clansmen to come in, Claverhouse moved swiftly into Badenoch, his force numbering around 2000 which was substantially less than the gathering at Dalcomera back in May. Claverhouse was also keen to reach Ballochie before he and his garrison were overwhelmed by Mackay and his army.

On 25 July, Mackay marched his army out from Stirling and arrived at Perth later that same day. Numbering around 3,500 men his force consisted of the Scots-Dutch Brigade regiments of Mackay’s, Balfour’s, and Ramsay’s, the newly raised Leven’s and Kenmure’s regiments, along with Hastings’ English regiment, and Belhaven’s and Annandale’s troops of lowland horse. Mackay had also been supplied with three leather guns that had been requested from the Countess of Wemyss.4

To support Mackay’s expedition around 1,200 baggage horses had been gathered along with supplies for a fortnight. This would have been enough to get them to Inverlochy and established while additional provisions would be shipped up to Loch Linnhe.

The race to secure Blair Castle

Lord Murray informed Mackay via letter that he had blockaded Blair Castle with a force of Athollmen and also sent a warning that Claverhouse was now back in Badenoch and preparing to move into Atholl.

On 26 July, Mackay and his forces marched out from Perth and headed for Dunkeld. Robert Menzies of Weem reported to Mackay that the Jacobites under Claverhouse were approaching Atholl. Mackay dismissed the reports of a Jacobite move into Atholl, believing that Claverhouse had insufficient strength. Instead, Mackay continued to make preparations for his march to Inverlochy, trusting in Lord Murray to continue the blockade of Blair Castle until he arrived and to hold Atholl for the government.

Later on the 26th, Mackay and his army reached Dunkeld, a small market town on the north bank of the River Tay where they established a camp for the night. An additional four troops of dragoons and two troops of horse were summoned from Perth and Stirling to reinforce his army. Lack of good forage had crippled a large number of the cavalry troops operating in Scotland and with the exception of Belhaven’s and Annandale’s troops, it is unlikely that many would have been in a fit state.

At midnight, Mackay received news from Lord Murray that the Jacobites were within three miles of Blair Castle and that he had been forced to abandon the blockade of the castle. Murray stated that he had withdrawn south to Moulin and had stationed 100 men to guard the Pass of Killiecrankie. Writing back to Murray, Mackay instructed him to hold the Pass and told him that he would be with him around afternoon the following day.

Mackay then ordered Lieutenant-Colonel George Lauder of Brigadier Balfour’s Regiment to take “200 choice fusiliers” drawn from the grenadier companies of the Scots-Dutch Brigade and advance and link up with Murray’s men and secure the Pass. Lauder’s detachment would march through the night arriving at Moulin around dawn on the 27th.

The narrow and strategically important Pass of Killiecrankie was described in the Memoirs of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheil:

This was a narrow path at the foot of a steep, rugged mountain, with a precipice and river below, and a high hill on the opposite side, where three men with great difficulty could walk abreast. It is several miles in length, and though the late Duke of Atholl has been at the trouble of making it passable by coaches and carriages, yet to this day, ane army might be stopped in its march by a few resolute men posted at the mouth or issue of it, and other convenient places; nor is there any other way to march an army into Atholl from the South but by this pass or defile.5

Claverhouse’s Jacobite army had moved south into Atholl and before nightfall on the 26th had arrived at Blair Castle, relieving Ballochie and his small garrison. The Jacobite army consisted of the Maclean’s of Duart, Macdonalds of Clanranald, Macdonells of Glengary & Keppoch, Camerons of Locheil, Macleans of Otter, Macdonalds of Sleat, Purcell’s Irish regiment and around 40 horse commanded by Sir William Wallace of Craigie who had accompanied Brigadier-General Cannon from Ireland. The Jacobite horse, like Mackay’s, were probably suffering from a lack of good forage.

Both armies settled down for the night some nineteen miles apart.

Weapons and tactics of Mackay’s army: Foot regiments of this period were comprised of musketeers, grenadiers and pikemen, with musketeers making up the bulk of the regiment. The musketeers and grenadiers in the Scots-Dutch brigade regiments would have been armed with the new flintlock musket which had superseded the matchlock musket in Dutch service. Hastings’ English regiment and the newly raised lowland regiments of Leven’s and Kenmure’s would have had a higher proportion of matchlocks than flintlocks and a higher ratio of pikemen. Mackay’s infantry battalions were trained to fire on the enemy by platoon firing, which in theory would allow a continuous delivery of fire from the battalion, however, fire control would often break down in the midst of battle.

The final manoeuvers

At dawn on the 27th, Lauder’s detachment of 200 fusiliers arrived at Moulin. Lauder found the Pass of Killiecrankie unguarded and Lord Murray’s men nowhere to be seen. He then continued on through the Pass to secure the far end and sent back a report to Mackay that the Pass was secure and that there were no Jacobites in the vicinity.

Just as Lauder was arriving at the entrance to the Pass, Mackay led his army out from Dunkeld and would himself arrive at Moulin at around 10 o’clock. Here Mackay was reinforced by Robert Menzies of Weem and his Independent Highland Company. Mackay also met Lord Murray who informed him that his men had gone off to save their cattle from the Jacobite highlanders and that he and his men would not accompany Mackay.

Mackay decided to rest his army for two hours and he sent another detachment of 200 men under Lieutenant-Colonel William Arnot of Leven’s Regiment to move through the Pass and reinforce Lauder’s detachment at the far end.

After their two-hour rest, and once Mackay had received news from Lauder that the Pass of Killiecrankie was secure, the forces were ordered to enter the Pass. Balfour’s Regiment led the way, followed by Ramsay’s and Kenmure’s. Belhaven’s horse along with Leven’s and Mackay’s regiments came next and they were followed by the baggage train guarded by Weem’s highlanders. Hastings’ Regiment and Annandale’s horse brought up the rear.

It would take the 3,500 foot, 100 horse, and baggage train around four hours to move through. At the most narrow points on the route, it was only wide enough for one man or horse at a time. Mackay’s men would have been sweltering in their woollen redcoats on that warm summer’s afternoon as they made their way along the tree-lined path that meandered through the Pass with the fast-flowing River Garry on their left-hand side.

One account claims that an Athollman named Iain Ban Beag Mac-rath took a shot from the opposite side of the River Garry at the government troops as they moved through, killing one horseman at the spot now known as ‘Troopers Den’.

Claverhouse sent a party of highlanders under Sir Alexander Maclean of Otter to attack Lauder’s detachment who had now taken up position near the settlement of Aldgirnaid (now Killiecrankie) when news reached him that the whole of Mackay’s force was now in the Pass and moving on Blair. In the banqueting hall of Blair Castle, Claverhouse held a hasty Council of War.

His professional lowland officers urged caution, stating that the army was outnumbered and too tired and hungry to fight efficiently against Mackay’s well-trained and seasoned troops. They argued that the army should withdraw and wait until the remaining clans were assembled. Of course, Mackay’s men could not be described as seasoned. The regiments of the Scots-Dutch Brigade had been depleted of their best soldiers and the rest of his force were mostly new recruits.

The clan chiefs led by Lochiel were bolder and insisted that they should fight. “Our men are in heart; they are so far from being afraid of the enemy, that they are eager and keen to engage them” Locheil exclaimed. The decision was then taken to march out and meet Mackay in battle.

Claverhouse led the Jacobite army out from Blair. Instead of following the direct road from

Blair Castle, he turned to the left at Glen Tilt, and making a detour round behind the Hill of Lude, passed the edge of Loch Moraig before following the Aldclune Burn down onto the lower slopes of Creag Eallaich.

After reaching the settlement of Aldgirnaid at the far end of the Pass, Mackay sent Lauder’s detachment and Belhaven’s horse forward to reconnoitre the road to Blair. From atop a tree-studded hillock near Aldclune, Lauder reported that he could see scattered units of the Jacobites moving towards them. This was Sir Alexander Maclean and his force that had been sent to attack Lauder.

Mackay concluded this was the Jacobite advance guard coming along the road from Blair and he began to deploy his force in a cornfield just beyond Aldgirnaid with his left flank guarded by the River Garry. Despite believing that Claverhouse would not oppose him in Atholl it was now becoming clear to Mackay that battle was imminent and he ordered Brigadier Balfour to begin distributing ammunition from the pack horses to the infantry.

Lauder now reported that the main Jacobite force was beginning to come into view on the heights to the right, which threatened the right flank of Mackay’s army. Mackay was then forced to redeploy his army, swinging it a full 90 degrees and sending it up a scarp covered in trees and thicket, past Roan Ruairidh House (now Urrard House) and onto a plateau between Roan Ruairidh and the lower slopes of Creag Eallaich, which was ‘ground fair enough to receive the enemy, but not to attack them’. On that bright summer afternoon on the Braes of Killiecrankie, both armies deployed for battle.

Battle of Killiecrankie

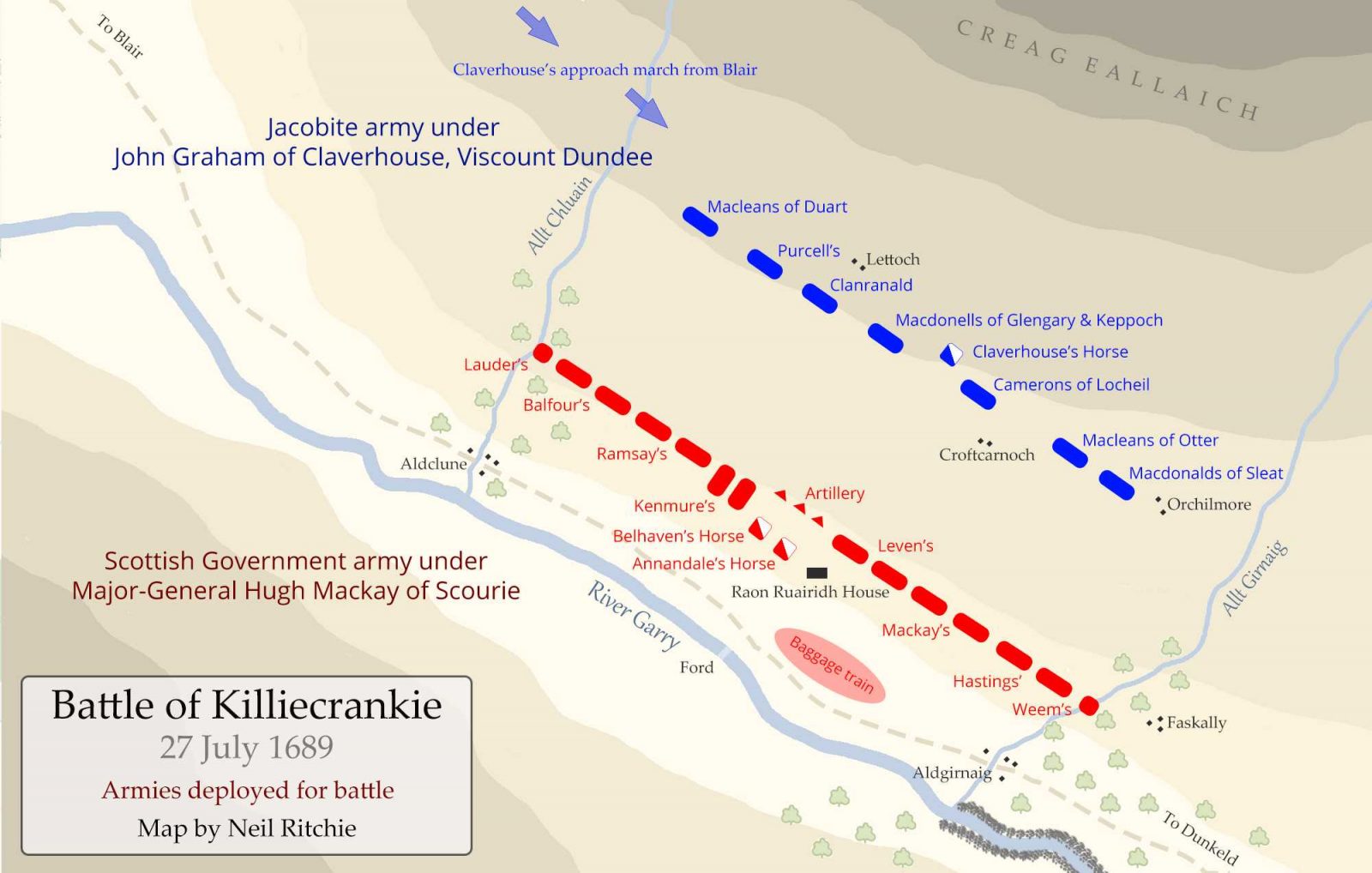

On his extreme right, Claverhouse placed the Macleans of Duart led by Sir John Maclean. Next to them stood Purcell’s Irish regiment conventionally armed with muskets and pikes. Macdonald of Clanranald’s men were next in line. Then came the Macdonells of Glengary and Keppoch with the Jacobite horse under Sir William Wallace of Craigie next to them. The Camerons under Sir Ewan Cameron of Locheil were next, then Sir Alexander Maclean of Otter’s Regiment. Sir Donald Macdonald of Sleat’s men stood on the extreme left. The Jacobite regiments were deployed deep in file to ensure that they would break through Mackay’s line.

Placing the highlanders on the slopes of Creag Eallaich would allow the highland charge to gather momentum and weight as they went downhill. This was similar to the battle of Mulroy in August 1688 when Coll Macdonell of Keppoch and his men had charged downhill and routed the Macintosh clansmen and Scottish government troops.

Claverhouse placed himself at the centre of the Jacobite army with the cavalry and addressed his troops in English which very few of the clansmen would have understood:

Gentlemen, you are come hither this day to fight, and that in the best causes… Remember that today begins the fate of your King, your Religion and your Country. Behave yourselves, therefore, like true Scotchmen. And let us, by this action, redeem the credit of this nation that is laid low by the treacheries and cowardice of some of our countrymen. In which I ask nothing of you, that you shall not see me do before you. And if any of us full upon this occasion, we shall have the honour of dying in our duty, and as becomes true men of valour and conscience.6

On Mackay’s extreme left and anchoring that flank was Lieutenant-Colonel Lauder and his detachment which was still positioned on the small hillock. Next to them was Brigadier Barthold Balfour’s Regiment. As Balfour commanded the army’s left wing, and Lauder was with his own detachment, command of the regiment fell to the next senior officer, Captain James Fergusson. Next to them stood Colonel George Ramsay’s Regiment. Next in line was Viscount Kenmure’s Regiment commanded by Lieutenant-Colonel John Fergusson. In the centre, Mackay placed the three leather guns under Captain James Smith.

Lord Belhaven’s troop under Lieutenant William Hamilton and the Earl of Annandale’s troop under Lieutenant William Lockhart stood behind the guns. The cavalry was under the overall command of John Hamilton, Lord Belhaven. The Earl of Leven with his regiment came next, then Mackay’s own regiment, commanded by his brother Lieutenant-Colonel James Mackay. Next in line was Colonel Ferdinando Hastings’ Regiment. On the extreme right, Robert Menzies of Weem’s highlanders held the flank.

Mackay’s regiments were split into two battalions each and stood three ranks deep with the exception of Kenmure’s which were deployed six deep. Deploying his line only three deep would maximise the frontage and firepower of his battalions at the expense of depth and stability. However, Mackay would have been trusting in his superior firepower to demolish the highland charge before it reached his lines.

Mackay also addressed his troops, making a short speech and addressing each

regiment in terms suited to their respective composition and character. He stressed the necessity of standing firm in the face of the highland attack and assured them that if they did so, they ‘should soon see the Highlanders turn their backs, but if, on the contrary, they suffered their line to be broken, they would be undone.’7

For around two uneasy hours both sides stood watching each other. Hoping to bring about a general engagement before darkness fell Mackay ordered Captain James Smith to open fire on the Jacobite lines with his three leather guns. Highlighting the ineffectiveness of the artillery it is claimed that a cannonball struck a highlander full on the targe, but merely knocked him over, shaken but otherwise unharmed. The guns soon fell silent as they disintegrated after firing three shots due to the fact that the gun carriages were too high.

A party of Camerons moved forward from their line and took possession of some buildings which they used as firing positions to harass Mackay’s Regiment. Mackay rode over and ordered his brother Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay to detach a captain and some men to dislodge them. Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay selected his nephew Captain Robert Mackay for the task which he executed with ‘great promptitude and gallantry, killing or wounding some, and chasing the rest back to the main body.’

While he was with his own regiment, Mackay went up to Donald Cameron, an officer in the regiment and the son of the Cameron chief Locheil and said to him, “There is your father, with his wild savages; how would you like to be with him?” “It signifies little,” answered Cameron, “what I would like; but I recommend it to you to be prepared; or perhaps my father and his wild savages may be nearer to you before night than you would like.”8

Mackay dreaded a night attack especially since most of his army were inexperienced and strangers to the highlanders and their way of warfare. On his part, Claverhouse was waiting until the sun sank behind the hills before he would give the order to attack. Intending for the gathering darkness to increase the fright and disorder of the charge.

Finally at around 8 o’clock, a full hour before sunset, Claverhouse gave the order to begin the attack. Barefoot, stripped to their shirts and yelling their Gaelic warcries the highlanders set off down the hillside and into the storm of musket fire from Mackay’s lines.

Mackay had instructed the officers commanding the battalions to commence firing at 100 paces and to fire by platoons so that the approaching highlanders were met with a continual rolling fire from along the lines.

The government fire took a dreadful toll on the advancing highlanders and as many as 700 are believed to have been felled by the musketry. The terraced terrain in front of Mackay’s men proved to be a great firing marker as evidenced by the high concentration of musket balls recovered from the terraces 30 or so paces to the front of the government lines.9

The government musketeers were equipped with bayonets which were a plug type and fitted directly into the barrel. The obvious drawback was that the musket could not be loaded or fired again while the bayonet was in place. It is unlikely that this had as much of an impact at Killiecrankie as some claim. Choosing the right time to fix a plug bayonet was crucial and fixing them too early might mean not being able to fire off another volley which could have halted the highland attack.

It would appear that many of Mackay’s men didn’t have time to fix bayonets before the highlanders were upon them. Mackay later stated: “the Highlanders are of such quick motion, that if a battalion keep up his fire till they be near to make sure of them, they are upon it before our men can come to their second defence, which is the bayonet in the musle of the musket”.10

During archaeological surveys on the battlefield fragments of grenades have been recovered indicating that the grenadiers among Mackay’s battalions lobbed their grenades at the mass of charging highlanders. They were typically used during storming operations so it is rare to find examples of their use on a battlefield.11

As the highlanders came running down towards the line of redcoats the Jacobite left wing advanced faster than the right. Lochiel’s Camerons shifted to the left and made a dash for Mackay’s own regiment, in which Locheil’s son served. Crossing in front of Leven’s men the Camerons were subjected to devastating flanking fire, losing around 120 men, but their attack continued.

Sir Alexander Maclean of Otter’s Regiment was also converging on Mackay’s Regiment, which, well-trained and handled, was able to inflict heavy casualties with disciplined musket fire before the highlanders, pausing only to discharge their own muskets, closed with them. Assailed from the front and flank Mackay’s Regiment was overwhelmed. With no time to fix bayonets, most of the regiment broke and fled, leaving Lieutenant-Colonel Mackay, some officers and a number of pikemen to be killed standing their ground.

Claverhouse led forward the Jacobite horse under Wallace of Craigie on an attack against the government artillery in the centre. For whatever reason, Wallace wheeled the cavalry to the left to join the attack on Mackay’s Regiment, leaving Claverhouse and only a handful of horsemen to charge the cannon. Captain James Smith and his gunners were cut down, with Smith receiving ‘many wounds to his head and body.’ Smith survived the battle.12

As the Macdonnells advanced on Kenmure’s Regiment which put down good fire, Mackay led Belhaven’s troop out to charge the exposed Macdonnell flank. Belhaven’s horsemen however panicked and fled and, ‘in the twinkling of an eye’, Mackay found himself in the middle of the battlefield with only his manservant by his side. Belhaven’s rode through Kenmure’s men which in turn caused them to break as well. Kenmure’s lieutenant-colonel, John Fergusson was killed after being abandoned.

Great palls of smoke swiftly obscured much of the battlefield and the evening air would have rung with the sound of clashing steel, gunfire, and screams and cries as the highlanders’ merciless blades performed frightful execution. “There were scarce ever such strokes given in Europe as were given that day by the Highlanders. Many of General Mackay’s officers and soldiers were cut down from the skull and neck to the very breasts; others had skulls cut off above their ears… some had both their bodies and cross-belts cut through at one blow”.13

On Mackay’s left wing, Balfour’s, Ramsay’s and Lauder’s detachment broke and ran when attacked by the Macleans of Duart, Macdonalds of Clanranald, and Purcell’s Irish regiment who charged downhill ‘like a stampede of cattle’.

Mackay stated that Balfour’s Regiment did not fire a single shot before running away. He also stated that only half of Ramsay’s Regiment fired on the highlanders, indicating that the other half ran before firing a single round or had nothing to fire upon to their front and were perhaps attacked on the flank following the collapse of Kenmure’s to their right. Colonel Ramsay was able to fight his way out and managed to cross the River Gary to safety.

Military historian Stuart Reid has speculated that Balfour, with the battlefield covered in smoke and not knowing what was happening on the right, believed that the battle was already lost and had begun to pull his troops back before the attack by the Macleans, Purcell’s and Clanranald came upon them. He certainly would have been concerned that if Mackay’s right had given way then the line of retreat back through the Pass would have been cut. This may explain why Balfour’s and half of Ramsay’s did not fire, since they were already pulling back before the highlanders had come into range. However, what may or may not have started as an orderly withdrawal quickly turned into a rout.

Lieutenant-Colonel Lauder’s detachment that was ‘posted advantageously upon the left of all, on a little hill wreathed with trees with his party of 200, of the choice of the army’ did as ‘little as the rest’ on the left wing. Lauder was able to escape the carnage on horseback and made his way back through the Pass of Killiecrankie. His men did not fare so well and were likely attacked by a number of Athollmen who were lurking around Aldclune, waiting to see which way the battle would go.

Brigadier Balfour was killed after being left alone following the rout on the left. He had been unhorsed and was attacked by three Athollmen near Aldclune. The most popular account of his demise claims that the Reverend Robert Stewart, minister of Balquhidder, attempted to save Balfour’s life but when he refused to surrender Stewart drew his broadsword and in one fell swoop sliced Balfour in half. The Balfour Stone 1.5 miles away in the Pass of Killiecrankie erroneously claims to be the spot where he fell. Captain James Fergusson and Brigadier Balfour’s son, Captain Bartholomew Balfour, were taken prisoner.

The highlanders pursued the fleeing redcoats back towards the Pass of Killiecrankie, stopping only to plunder the government baggage train that was situated in the cornfield below the battlefield, allowing many of Mackay’s men time to escape.

Donald McBane, a Scottish government soldier from Inverness, described his experience of the battle and his epic escape some years later:

At last they cast away their muskets, drew their broadswords, and advanced furiously upon us, and were in the middle of us before we could fire three shots apiece; broke us, and obliged us to retreat. Some fled to the water, and some other way; (we were for the most part new men.) I fled to the baggage, and took a horse, in order to ride the water there follows me a Highlandman with sword and targe [shield], in order to take the horse, and kill myself. You’d laugh to see how he and I scampered about. I kept always the horse between him and me; at length he drew his pistol, and I fled; he fired after me. I went above the pass, where I met with another water, very deep. It was 18 foot over, betwixt two rocks. I resolved to jump it; so I laid down my gun and hat and jumped, and lost one of my shoes in the jump. Many of our men were lost in that water, and at the pass. The enemy pursuing hard, I made the best of my way to Dunkel [Dunkeld] where I stayed until what of our men was left came up; then every one went to his respective regiment.14

The spot where McBane claimed to have jumped across the River Garry is known as ‘Soldier’s Leap‘. McBane had also been present at the battle of Mulroy the year before, and there too he had been forced to flee from the highland charge.

Around half of Leven’s Regiment remained on the field despite the chaos all around. Mackay rode over to this ‘small hep of red coats’ and found the Earl of Leven and most of his officers still present. Mackay praised them for their steadfastness but instructed them to be ready to receive the enemy who he expected to attack again at any moment.

Mackay then rode on to Hasting’s Regiment which was still largely intact on the right wing alongside Weem’s company.

Macdonald of Sleat’s Regiment had descended upon Hastings’ men who had initially stood their ground, firing disciplined volleys and inflicting heavy casualties among Macdonald’s clansmen. However as Mackay’s Regiment gave way to his left, Colonel Hastings was forced to pull his men back and refuse his now exposed left flank, swinging it back ‘like a barn door’. This allowed the hard-pressed Macdonalds to pour into the gap that had now appeared and they rolled into Mackay’s fleeing regiment before making their way to loot the baggage train. Colonel Hastings then reformed his regiment and moved them back to their original position on the battle line.

Claverhouse observed that Macdonald of Sleat’s attack on Hastings’ Regiment was faltering and he rode over to take command of the situation personally. Crossing in front of Leven’s remaining men he was fired upon and a round struck him below his breastplate and went into his stomach and he fell from his horse mortally wounded.

A group of Jacobite officers attempted to carry Claverhouse from the field but they were met with musket fire and were forced to abandon him where he fell. Claverhouse’s naked body would later be recovered from the field after dark. He had been finished off with a pistol shot to the head, likely by someone on his own side.15

Some of Mackay’s officers later claimed to have seen Brigadier-General Alexander Cannon taking command of the Jacobite forces that remained on the field, indicating that Claverhouse had fallen.

Mackay now gathered what remained of his army at Raon Ruairidh House and considered establishing a redoubt there. Sending his severely injured nephew, Captain Robert Mackay, to gather as many officers and men as he could rally, Mackay initially intended to remain on the field until dawn with Hastings’ Regiment, the remains of Leven’s, and Weem’s highlanders, around 600 men in total.

Writing to the Duke of Hamilton two days after the battle, Mackay praised those who had stuck by him: “…in short, there was no regiment or troop with me, but behaved like the vilest cowards in nature, except Hastings and my Lord Levens, whom I most praise at such a degree, as I cannot but blame others, of whom I expected more”.

As darkness fell the remaining Jacobites were gathered together by Brigadier-General Cannon and began to pull back towards Blair Castle. Mackay now decided it was time to extract his remaining forces from the battlefield and led by Robert Menzies of Weem they descended the slope behind Raon Ruairidh House, crossed the cornfield and forded the River Garry.

A couple of miles away they were joined by Colonel Ramsay and around 200 men that he had managed to rally. Weem then led them over the hills to his home of Castle Menzies. From there Mackay and his men carried on to Drummond Castle before making their way to Stirling and then Perth. Mackay left behind perhaps as many as 1,800 killed, wounded or taken prisoner. The Jacobites had lost between 700-800 men.

Aftermath

The carnage on the Braes of Killiecrankie would have been horrific, with perhaps over 2000 men lying dead or dying. It certainly shocked even the most hardened of contemporaries.

The enemy lay in heaps almost in the order they were posted; but so disfigured with wounds, and so hashed and mangled, that even the victors could not look upon the amazing proofs of their own agility and strength without surprise and horror. Many had their heads divided into two halves by one blow; others had their sculls cut off above the ears by a back-stroke, like a night-cap. Their thick buff-belts were not sufficient to defend their shoulders from such deep gashes as almost disclosed their entrails. Several pikes, small-swords, and the like weapons were cut quite through, and some that wore skull caps had them so beat into their brains that they died upon the spot.16

Brigadier-General Alexander Cannon took command after the death of Claverhouse and led what was left of the Jacobite army back to Blair Castle. Cannon reported that the dead were buried on the field the following day, possibly by government prisoners. Iain Lom MacDonald, an eyewitness and poet mentioned: “On Killiecrankie of thickets, Are many graves and stiff corpses, A thousand shovels and spades were requisitioned for covering them”. Claverhouse’s body was recovered from the field and taken back to Blair Castle before being interred at St Bride’s Kirk on the grounds of the castle.

The government in Edinburgh learned of the defeat at Killiecrankie late in the evening of the 28th. When King William heard the news days later he is said to have remarked that Claverhouse must have been killed in the battle otherwise by now he would be master of Edinburgh.

A few days after the battle, Cannon gathered the Jacobite forces and marched south from their base at Blair Castle to Dunkeld, spending two days there where they received reinforcements, including men from Glencoe and the Appin Stewarts. Further clansmen were assembling at Braemar, and the Jacobite forces in Scotland under the command of Cannon soon numbered around 5,000.

Instead of marching on a lightly defended Perth with his full force, Cannon sent a party of 300 men to secure supplies that had been stockpiled there for the government forces. On 1 August the party was taken by surprise by government cavalry led by Major-General Mackay, with around 100 killed or captured.

Fearing government forces would be too strong in the Perth area, Cannon marched his army north to Braemar to collect the additional reinforcements, all the while pursued by Mackay’s mounted force.

On 21 August, Cannon’s Jacobite army attacked the town of Dunkeld which was held by the Earl of Angus’ Regiment. The Jacobite attack was repulsed and they withdrew back to Blair Castle where the army soon dispersed to gather in the harvest.

By 25 August, Major-General Hugh Mackay, this time taking no chances, had assembled a formidable military force at Perth comprising seven infantry regiments, two regiments of horse, two of dragoons, and three Independent Highland Companies. Setting out on the 26th, Mackay marched his army into Atholl, passing the site of his defeat at Killiecrankie a month earlier and arrived at Blair Castle on the 28th where he established a 500-strong garrison.

In April 1690, the Jacobite clans gathered again for a new campaign under a new commander, Major-General Thomas Buchan, but were defeated by Scottish government troops under Sir Thomas Livingstone at the battle of Cromdale on 1 May 1690 which effectively ended the first Jacobite rising. Scottish government operations continued against the Jacobite clans until 1692, with the most infamous of these actions being the Massacre of Glencoe.

Historic Environment Scotland has included the battle of Killiecrankie in their Inventory of Historic Battlefields describing the battle as “significant as it is the opening battle of the first Jacobite Rising in Scotland. In later years their success at Killiecrankie would be a continual inspiration to Jacobites in Scotland, even though the loss of Dundee in the battle fatally undermined their cause. It also highlights the devastating effect a well-executed Highland charge could have on an enemy, and also displays the first of numerous technological and tactical developments by the fledgling British Army in this period.”17

Notes:

- Stuart Reid, I Met the Devil and Dundee: The Battle of Killiecrankie 1689 (Nottingham: Partizan Press, 2009).

- John Drummond of Balhaldie, Memoirs of Sir Ewen Cameron of Locheil.

- David Stevenson, Highland Warrior: Alasdair MacColla and the Civil Wars.

- On 14 July 1689, the Privy Council of Scotland instructed Margaret Wemyss, 3rd Countess of Wemyss to “lend some of your leather gunnes to General Mackay for this present expedition to the Highlands, wher no other artileiarie can be carried.”

- Balhaldie, Memoirs.

- Mark Napier, Memorials and Letters Illustrative of the Life and Times of John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount Dundee.

- John Mackay, The Life of Lieutenant-General Hugh Mackay.

- Ibid.

- Reid, I Met the Devil and Dundee; Battle Of Killiecrankie, Canmore.

- Hugh Mackay, Memoirs of the War Carried on in Scotland and Ireland, 1689-1691; After the battle of Killiecrankie, Mackay is said to have invented the ring bayonet that allowed soldiers to load and fire their muskets with the bayonet attached.

- Battle Of Killiecrankie, Canmore; The Courier, 29 March 2021.

- Register of the Privy Council of Scotland, 1689.

- Memoirs of the Lord Viscount Dundee.

- Donald McBane, The Expert Sword-Man’s Companion; Donald McBane had originally joined Ludovik Grant’s Regiment at Inverness but was later drafted into one of the regiments of the Scots-Dutch Brigade.

- When some of Mackay’s officers viewed Claverhouse’s body sometime later at Blair they noted that he had a wound above his left eye as well as the wound to his stomach.

- Balhaldie, Memoirs.

- Historic Environment Scotland, Inventory of Historic Battlefields: Battle of Killiecrankie: http://portal.historicenvironment.scot/designation/BTL12

Article first published on 29 July 2022

Cite this article: Ritchie, N. (29 July 2022). Battle of Killiecrankie and the Jacobite Rising of 1689. https://www.scottishhistory.org/articles/battle-of-killiecrankie/